The morning after the election I rode my daily Metro-North to New York City and listened to the Anna Karenina soundtrack. I was drawn to its purposeful movement and conspiratorial urgency, noting the irony of its Russian subject matter. I watched the fall landscape pass through the glass reflection with more poignancy than usual.

The reality of Trump’s victory was a car crash of international proportions; I could not keep from looking away and reading more about it. There was a map of Millennial voters, countdowns to the 2018 mid-terms and thought-pieces upon thought-pieces, one even declaring it was good for Democrats in the long run. The term “Resistance” was formed. On Twitter, the accounts I followed were pledging to work harder, be better and get engaged at whatever level they could. It was all a heart-warming echo-chamber.

I wasn’t immune from Twitter’s rare burst of sentiment and didacticism. I wrote a couple drafts.

After talking to some friends and fellow artists, I can say that many of us had the same reaction. Everything is more serious than before. For a generation who had mainly spent its maturing years under the stability of Obama, the Trump reality was our first real disillusionment. Progress was abruptly halted, and Trump was hell-bent on putting the thing in reverse.

The idea of progress was thoroughly fucked. Now my generation had to deal with overt racism, science deniers with a platform, and corporate cronies living among us. We really thought we were going to be the ones to hurdle the obstacles of those who came before us, and change the world.

My daughter was born the day after. I was hoping to welcome her into an America with a qualified woman president, not a self-professed pussy grabber. Whenever I think about this, it’s always with the Arcade Fire lyrics from Suburbs: “So can you understand/ Why I want a daughter while I’m still young/ I want to hold her hand/ and show her some beauty/ before all the damage is done/ But if it’s too much to ask, if it’s too much to ask/ Then send me a son.”

With the swells of Dario Marianelli’s soundtrack urging me onward, I, too, made a private pact to devote myself wholeheartedly to more meaningful pursuits. I’m just an aspiring novelist, what can I do in these political times? I devised to turn the series of loosely-related short stories I had just finished the week before into a fully-fledged, very ambitious, probably naïve attempt at the great American novel.

The subtle connection between certain characters’ mindsets and populist movement, I decided, would become a major, if not main force. The thought was there would be skits that put the novel’s characters into a broader context, similar to the one-off chapters in John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath, between the focus on the Joad family. I outlined a scene where, as a physical manifestation of his misdirection, Trump uses a magician showmanship in his nightly seduction of Melania, who speaks only in quotes from Michelle Obama. Another scene features Putin vlogging instructions to operatives for their misinformation campaigns.

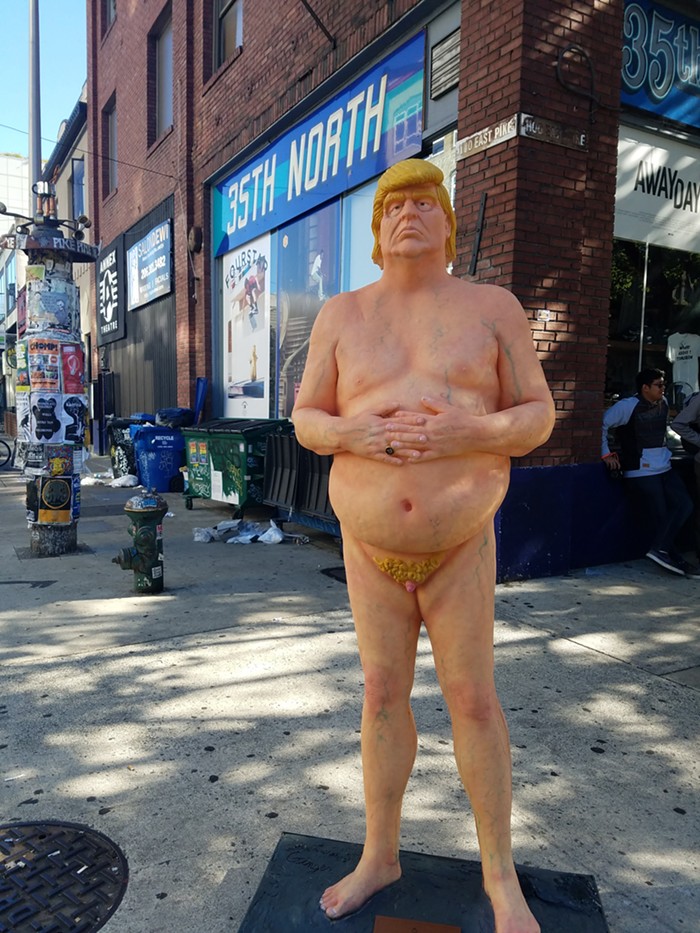

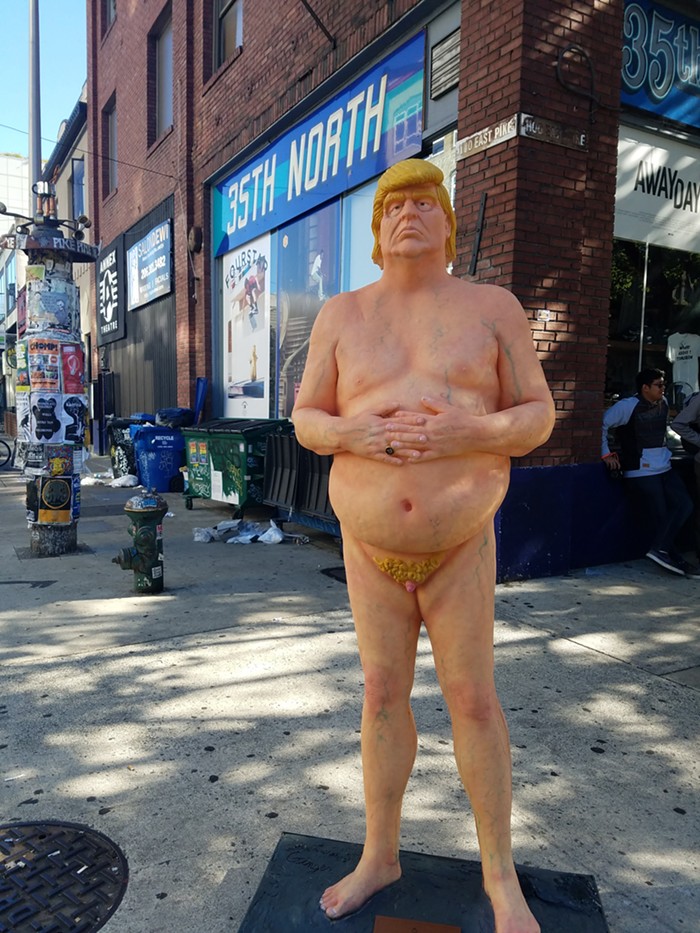

I wasn’t alone in this impulse to focus on political matters in art because of Trump. Even leading up to the election, artists attempted to satirize, condemn, or humiliate Trump. The image that jumps out me to the most is the naked wax figure, derisively depicting a corpulent stomach and micropenis.

(Source: The Guardian)

Since the election, I’ve seen an emergence of American fiction. There’s been a proliferation of pieces focusing on politics, and borrows its characters from the prominent figures of the White House first family and administration—which, today, is virtually synonymous. I am a proponent of making literature prescient and relevant to its time, but the question should be asked, “What do these pieces accomplish?”

The Sketch-Comedy Response

One of the first fictional pieces I read regarding Trump was “Jared Kushner’s Fight Flight” by Luke Mazur. It turned out to be one of a series of politically-driven pieces Mazur write online literary magazine, The Awl.

“Everything Changed”

I asked Mazur what prompted the politically-driven fiction. At the time of the election, Mazur was prepared for a Hillary Clinton presidency. He was interested in how the conservative members of the Supreme Court would transition. “But then hell day happened and everything changed,” he told me. “I couldn’t write for a long time. Nothing I had to say felt important enough.”

Mazur’s pieces are quick slap-stick of the administration in screenplay format, like a sketch-comedy. They have innocuous titles like “Jared and Ivanka Plan a Summer Trip” and “Jared Kushner Breaks the Ice,” but they all reference major headlines from week to week: The Pope Francis visit, the leaks, Jared’s infamous Kevlar-wear picture, the James Comey testimony.

(Source: Market Watch)

The pieces mock the caricatures that represent the administration. Ivanka is heartless and power-hungry, often depicted through the screenplay’s brackets: “IVANKA [violating her own rule to never validate a loved one] That’s fun, Jared.” Jared is naïve and in over his head. Reckless and racist, incoherent Bannon, deceitful Kellyanne Conway, and imbecile Spicer all make appearances to boot. With its central characters Jared and Ivanka, the stories play up their opulence outrageously and plausible dysfunction in their relationship.

The apparent dysfunction in Trump’s life is a common target for fiction writer’s responding to Trump. Angela Mitchell’s “You Are Not Like Other Children,” from Necessary Fiction, imagines the isolation, neglect, and loneliness of Barron, as if the lavish qualities of his mother and his life are something inherently worn, like skin. Mitchell construes Melania’s skin treatment as a requirement from Trump, who she reacts to as a predator she lost her tail to. Barron, in this version, doesn’t mind when his father is gone. He even fantasizes that he’s born fatherless, simply replicated by his mother, so the two of them can “smell the enemy,” (the Donald), hiding from him “in plain sight.”

(Source: House Beautiful)

Mitchell’s story has no discernible political purpose. She sets her narrative with characters, furnishings, fixtures of Trump and his family’s life. In the end, she uses them only to make a vague conclusion about the demeanor of Trumps, and the slight distinction between those born so and married in. But at worst, it feels like the Mitchell used Trump-mania for attention, and delivered little more than an intrusive take on a pre-teen.

Mazur’s pieces do more than seed dysfunction in the mind of the public. They capture a trove of political details a weekly basis. Sometimes a point is made merely by the inclusion of a piece of evidence. Suggestive intents of Comey’s email before the “October Surprise,” and Rebekah Mercer back channels, for example. It’s a diving board for eager citizens to pick out significant details out of the septic deluge, many of it, by sheer volume, goes unnoticed.

Is it important that this prompts a litany of Google searches and more detail from journalistic sources? Then, why get it from a piece of fiction instead of Politico? The same facts and theories litter most everyone’s timelines and News updates, why not go directly to the source?

Entertainment is one answer, but probably not a good one. CNN and Fox News have made high-rating, political entertainment for their disparate audiences with disastrous results. Donald Trump, the reality television star himself, is now the President. It’s hard to argue that Trump’s TV savvy, with the fact his original campaign’s intent was possibly just a publicity stunt, and CNN’s free broadcasting of his platform didn’t bring us to where we are today.

Perhaps the main goal for Mazur’s pieces is to capture self-awareness of the main characters as they commit themselves to their unique, damning motives. Complicit Ivanka cooly remarks, concerning Comey’s notice of investigation into Clinton, “His letter was just pretext for racists who were never going to vote for her anyway.”

Kellyanne Conway gets a similar treatment. In “Jared Breaks the Ice,” she brags, “I know how to campaign to women who hate other women.” And in a game of two truths and a lie, Sarah Huckabee Sanders says, “[truthfully]: Number two. I only got this job because of who my father is —”

It’s not a whimsy that the series focuses on Kushner—older pieces took on Merick Garland and Paul Ryan as their narrative’s focus before Mazur landed on Kushner. Naïve Jared, the dilettante, trust-fund baby-faced caricature is viewed as less blatantly less aware of the impact of his actions.

“Finally, I settled in on Jared. I just thought, in some ways, he was stuck in this situation, that probably he enabled, but also probably he never intended,” Mazur tells me. It makes sense on the surface. As a counterpoint to the rest of the administration, Jared appears in-over-his-head and swept along with collusion, nationalism, and fascism of the people surrounding him.

Whether this self-awareness is factual or not, we will never really know—but it is assuring amidst all the reports, rumors and false news. In fiction, we can escape into a sense of certainty.

Mazur creatively highlights his certainty by jamming as many conclusive statements into description and actions brackets. Ivanka juices what the narrator informs us is “a stack of paperwork that confirms she and her husband profited immensely from collusion and money laundering.” She also is caught “[while texting her mainstream media back channels that she and JARED orchestrated her father’s pivot on the DREAMER children].”

Putting these phrases in the brackets, functioning as the writer’s direction, adds another layer of authority to the claims. It’s one of the ways authors are dealing with the talking about politics in the age of Trump.

To Mimic or Mock? How Fiction Addresses Shifting Political Realities

Authors in less flexible genres, like political thrillers, aren’t as equipped to deal with the new circumstances as Mazur’s fiction. False Flags author, John Altman laments that Trump barrels through rules and expectation on a daily basis, outdoing any unbelievable fiction plots. He writes in his LA Times article, “One might argue that Trump is doing the author’s work for him. But when a story feels implausible, it doesn’t work.”

And with Trump’s disregard of the rules comes a constant flux political realities. Altman writes, “Recognizing that I was powerless to predict the direction of these particular geopolitical winds, I inserted only a single line: “Israel’s greatest ally, the United States, blew hot and cold.” Any attempt at realistic relevance is basically futile.

Altman is forced to respond to the outrageous headlines with just a nod. Unrestricted by his genre, Mazur response is to push the absurdism to its logical conclusions. Of course, this is the efficacy of satire—it highlights the underlying truths by pulling them to the surface, often with absurd, but fair conceits, like Jonathan Swift’s A Modest Proposal arguing for the eating of the children of Ireland.

“I found I could only write if I threw my voice, so to speak,” Mazur says. “If I wrote satirically.” This was the same logic behind the political scenes I planned to add to my novel. I felt these highly influential events need to be included to really capture what 2016 and 2017 were like, but how? Do readers want to read, basically, what they already know in a novel published a year or two after the fact?

But is there even any space for satire in America’s current political climate, current or after-the-fact? The factual plot points surely outdo Altman’s brand of believable suspended disbelief. Many more are becoming more transparently vile than Mazur’s statements of fact.

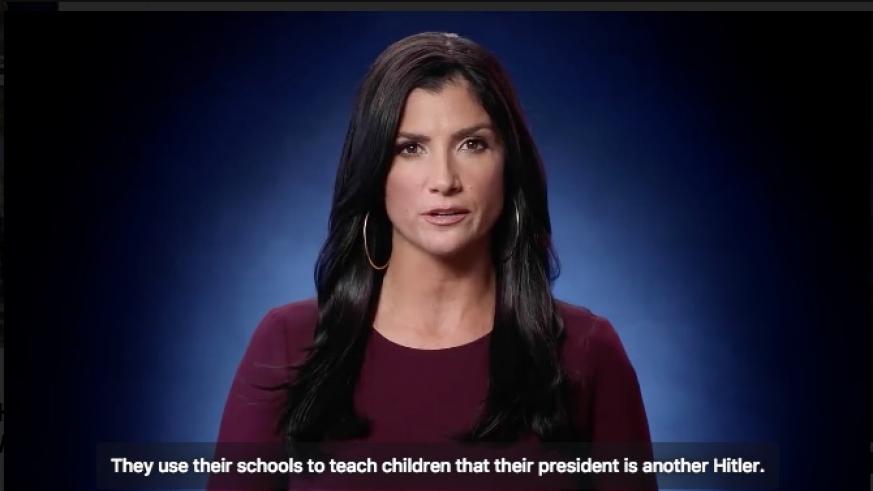

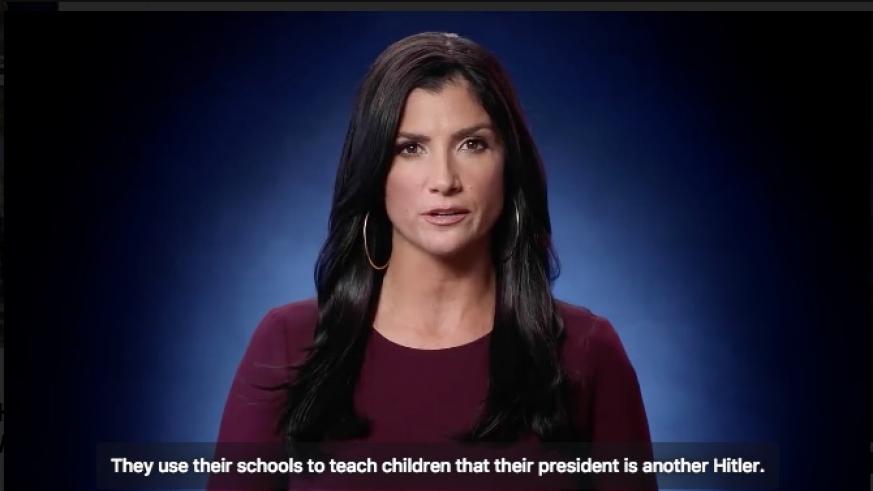

(Source: Metro)

Take, for example, NRA’s suggestively violent political ad to sell guns the same month a citizen shot a politician at a baseball field. Or Trump’s team trying to blackmail TV show hosts over an apology. Or take the used toilet paper-length and -quality healthcare bill and the circus around it. Take the Travel Ban. Fuck all of it.

Mazur’s comedy and satire might have relevance if the motives were even as thinly veiled as their already tissue-paper surfaces: law enforcement instead of threatening dissent, national safety instead of national identity, or fewer healthcare restrictions. Taking an argument and poking holes in it a worthy cause, as is mocking the idiots who make it. But 2017 has been a exercise of the phrase “stranger than fiction.”

(Source: DailyWire)

You can’t make up how freshly appointed White House Communication Head, Anthony “The Mooch” Scarramucci, called reporter Ryan Lizza and leaked the fact that Reince Priebus would be fired while ranting about leaking, then saying he’d like to kill the leakers and fire the entire White House Communications staff, and then adding that White House Strategist Stephen Bannon is there to “suck his own cock.” All of it on the record. He later half-assed an apology and blamed the reporter.

If that isn’t the slap-stick Communication’s version of Orwell’s ironic Ministry of Truth, I don’t know what is.

I was in Brazil when I read it. I only had Wi-Fi when I was in the house I was staying at, so when I casually opened up Twitter and was hit with an onslaught auto-fellatio tweets from the media as well as everyone else, I said aloud, “What the fuck is going on?” I had that same reaction three times over the course of my ten-day trip.

When I read Scarramucci’s rant, I was captivated by his ability to so blatantly contradict himself and fuck up his tenure so grandly. I laughed. I read in disbelief. But that underlying feeling of anxiety surged. You know the one–the one that comes that comes with the knowledge that aggressively idiotic people are at the helm of your country.

No piece, by Mazur or anyone else, can outdo what Scarramucci said. And unfortunately for the authors and the public, there is no outdoing the Trump administration in terms of irony, hypocrisy and utter absurdity.

I see it all the time on Twitter, people commenting: It feels like we’re in one of Thomas Pynchon’s or Don Delilo’s exaggerated plotlines.

Then follows the comment, whether posted or in our heads, “but this is all real.”

The Prophets and the Doomsdayers

Ben H. Winters, author of The Last Policeman, makes a similar comparison of the nature of reality to literary works. To him, it feels as if American were now living in a separate offshoot of reality, akin to speculative fiction. “Even as it begins, the Trump presidency feels like an absurd and highly unlikely counterfactual,” he writes in his introduction to a Slate’s fiction series response, The Trump Story Project. And later in a podcast, Winters says, “It really reminded me, and the feeling reminds me still, of works of speculative fiction, the kind of what-if novels like The Plot Against America and The Yiddish Policeman’s Union, where the writer takes some specific historical event and undoes it or changes it in some dramatic way to imagine what would things have been like if our history turned out differently.”

The election of Trump, to Winters, was such an event. “History was supposed to go a certain way, and suddenly, strikingly, it had gone this very different way.”

(Source: CNN)

The Trump Story Project tells cautionary tales of the near future.

The first in the series, “The Daylight Underground,” takes an interesting look at the use of identity in Trump’s nationalism. Héctor Tobar’s narrator explores, as well as embodies, the different types Trump and his supporters have vilified over the course of his campaign and administration. James is a political science graduate student and Mexican-American. An academic and Hispanic. James anticipates the unexpected (to racist nationalists) concessions he will have to make. He pours over an English dictionary, cherishing the words and phrases he will no longer use. He wonders about the food on the other side: “In our daydreams, we worry. Yes, the Mexican food will we better (by definition); but will we find a decent Starbucks over there?”

The piece chooses symbolism over realism—the administration has chosen to deport even American-born Mexican-Americans. The point, though, is that any label is reductionist. In reality, we can hardly imagine the complexities of identity—political, cultural and genetic. The piece references people “ripped from” their people and communities, but it ends with the image of a cactus in the desert whose roots are tangled and gnarled, resilient, perpetually pushing deeper.

It’s a similar moral to Lauren Beukes piece, “Patriot Points,” which dissects the bias and hypocrisy of Trump’s nationalist identity policies and stances with precision and cutting comedic timing. The entire piece is written as a business scheme thinly-veiled as a survey for citizens to apply for Patriot Points to be used for discounts and TSA Precheck approval. One question asks, “Have you performed military service?” with the following options:

“Yes, I am currently serving my country: +100

Yes, I served, proudly: +20 for every tour of duty

(-50 for PTSD and other disabilities or injuries that drain the country’s resources)”

The piece echoes the worries of real-life circumstances. The proposed Muslim database, the violation of the Hatch Act in the GOP’s voter fraud “investigation” as well as the absurdly leading survey, with two choices: “I stand with President Trump” or “I believe Democrats and the fake news media.” Again, one of the cases in which reality somehow outdoes satire.

“Patriot Points” and “The Daylight Underground,” the latter especially, are alarms with the warning signs fully delineated. Winters’ own piece, “Fifth Avenue,” is an even more moralizing, this one about the dangers of attacking the media and limiting free press. In this reality, it’s 2020 and Trump is already killing journalists in broad daylight.

The setting speaks to an already missed sign from his campaign: Trump’s infamous quote “I could stand in the middle of Fifth Avenue and shoot somebody and I wouldn’t lose voters” was only a taste of his violence, and America’s ability to allow it.

(Source: YouTube)

Now he’s executing an emolument-beat writer who knew too much. The writer at the center of it recalls America’s swift descent from democracy to totalitarian state with today’s popular consolatory humor. The narrator says, “The funny thing, not funny ha-ha, more like death of a republic funny—is that nobody cared.” Later, as death approaches, he reflects more seriously, “We are always one moment away from what-was-always-becoming what-will-never-be-again.”

“Fiction has this special power. It has the power to clarify, to galvanize, to prophesy, to warn,” Winters said about the Trump Story Project in the podcast. To achieve this, in today’s circumstances, Winters turned to authors who “played with the idea of reality.”

In the past, fiction’s playful and imaginative tweaking of reality has often led to powerful results. Salman Rushdie uses the fantastical elements of magical realism to broach the political cleansing in India. And more recently, Bakhtiyar Ali employed it in his novel, I Stared at the Night of the City. Agri Ismaïl points out, Ali employs magical realism as a way to satirize the political and social realities comprehensively without being censored.

But how are contemporary American fiction writers using the tactic?

On one hand, the stories often fast-forward reality to harsher, sometimes apocalyptic terms. After the election, there was a surge in readership of dystopian books, like George Orwell’s “1984” and Sinclair Lewis’ “It Can’t Happen Here.” One could argue that fiction, like Slate’s project, is filling this function with the terms understood today.

On the other, the tactic offers an unrealistic hope. Many pieces in the collection have something in common with the tweets I read the morning after the election. They are earnest and insightful stories that warn and preach to the choir. At their worst, they have escapist elements.

A djinn miraculously halts a deportation in “Clay and Smokeless Fire.” In “Fifth Avenue,” the journalist cries out to Kushner’s saner head to prevail. “Please, Jared. For fuck’s sakes—” We can all admit it, no matter how meek-looking this rich white boy who voted for Obama is, he’s an essential piece of Trump’s exploitative administration. James, from “The Daylight Underground,” literally escapes a collection center with such ease that conflict is clearly symbolic for alienation of citizens, rather than concrete deportation. Even Mazur’s weekly series comforts readers with a semblance of certainty, instead of the craze of paranoia; questions without discernible answers.

Lucid Dreamers

J. Robert Lennon’s piece, “A Museum of Near Misses,” is The Trump Project’s final story, and in my mind, an important counterpoint to the series. Set in an alternate universe in which a speculative fiction writer who made it big with a story about Trump actually getting elected is sent to purchase a portrait of the failed candidate from the Museum of Near Misses.

The majority of the story is located in a nearly abandoned “flyover state” in an alternate reality. The audience is comforted to hear that Trump lost the election, had to pay the women he assaulted, and was exposed by the Russian blackmail as a sexual deviant; “…it was clear in hindsight, [he was] utterly unelectable.”

The narrator adds to the irony, saying, “things didn’t happen for good reasons, I would have argued, and there was no need to dwell on what might have been.” J. Robert Lennon is the narrator’s name. Author and narrator know their real audience and intentionally turns them away from the escapism of nostalgia for what could have been.

Isn’t it, partly, the same impulse that urges a portion of the population to choose to make America great again? In the minds of Trump voters, both enthusiastic and hesitant, there was the plan to put the country “back on track.” For some, that track diverged at the 2008 election, some in the ‘90s, others in ‘50s, with a long list of gripes: Obama allowing jobs to be shipped overseas, feminism’s subversion of the traditional family unit, the sexual revolution, the teaching of evolution and the exclusion of religion in schools, and on and on. And then there are those that long for a time before their lifetime (“when this was a Christian nation”). When reality appeared to match their ideals. This mix of nostalgia, regret and righteousness is a dangerous one. It makes people desperate and look past one another. They’re ideals that don’t take into account the people excluded, disenfranchised or discriminated against.

(Source: DailyMail)

For my upcoming novel, I use the concept of Sehnsucht, a German word combining intense desire and intense missing of something, often difficult to say what it is. Christians might recognize it from C.S. Lewis’ writings. He calls it, “desire for we know not what,” which, for him, proved the reality of God and heaven. If there’s a desire that cannot be satisfied here, it means there is another place that will.

There is no political haven, in the past, the future, or an alternate dimension, where Clinton won the election. (At the same time, it’s important to measure the real damages that could have been avoided. The lives of the vulnerable, the exploited, the outsiders, the poor, would be better protected under Democratic policies.)

The story’s J. Robert Lennon returns to reality through a wing of the museum like Narnia’s wardrobe, less icy, but much shittier.

The urge to escape into the past grabs him: “Perhaps I could have turned back—retraced my steps, found my way past the jet and the statue and the horseshit and the custodian, and returned to the world from which I came.” But instead he acknowledges his mistake and provides a warning—this one, his audience needs to hear, “But I don’t think so. I think my fate was sealed when I beheld the painting, or when I answered my former friend’s call, or earlier still, when I elected to live a life of self-deception, a life dictated not by reality but by the seductive and shapely contours of fiction.”

Fiction is not inherently comforting, and in time like these it has an obligation not to be. It should confront us, the expected audience, at every turn. Especially when it’s easy to reach for comfort in all the helplessness to the gears of history repeating itself, even if that comfort is wishful thinking, or merely being right.

“I’m not from here,” says J. Robert Lennon, the character, capturing this feeling with his own sense of Christian sehnsucht. “Where I’m from, we clearly did something right, be damned if I know what it is.” In “The Daylight Underground, Tobar’ narrator quotes James Joyce’s character, Stephen, from Ulysses, read off another character’s tee-shirt: “History is the nightmare from which I am trying to awake.”

The difference reminds me of Jonathan Lethem’s analysis on Joyce and Pynchon. He writes, “In Joyce’s formulation, history is a nightmare from which we are trying to awake. For Pynchon, history is a nightmare with which we must become lucid dreamers.”

Our goal should not be trying to wake up out of this reality; there is nothing outside of it. Instead, despite our helplessness, we should seek agency in the little things we have control over knowing there is no salvation at the end of it, no utopia waiting at the end of a series of correct decisions.

(ACLU Lawyers quickly respond to rushed travel ban, New York Times)

The good news is people in real life are taking protests to the streets. Journalists are active, breaking stories. And ACLU lawyers worked overtime to defend the rights of the exploited and vulnerable.

Do American fiction writers have a part to play?

I don’t know. I don’t think I’ve read one yet that’s shown that it really does. J. Robert Lennon’s piece could be the introduction to the serious fiction that needs to be written and read.

The Age of Trump puts fiction writers in a difficult position. We all feel that what we were working on before was futile. Then, in an attempt to be relevant we dove headfirst into didacticism and overt mockery.

I don’t think it’s the answer. Months later, I decided the political slant of my novel didn’t have any efficacy. Instead, I’ve decided to turn its focus inward in hopes of questioning the personalization we’re comfortable with and the layers of self-satisfaction we protect ourselves with. I’ve let the connections remain subtle.

If political, then our fiction needs characters who really are deported, held at the gates, beat up for their identity. We need to see the cost. Our fiction needs to fuck with us, the probable reader. It needs to seriously and bitterly ask the questions at the heart of the American experience so maybe we can come up with a better answer tomorrow than the one we have today.